2024 GS P1 Solution, PYQs Solution

Q.1. Introduce the literary sources for the study of Ancient Indian History.

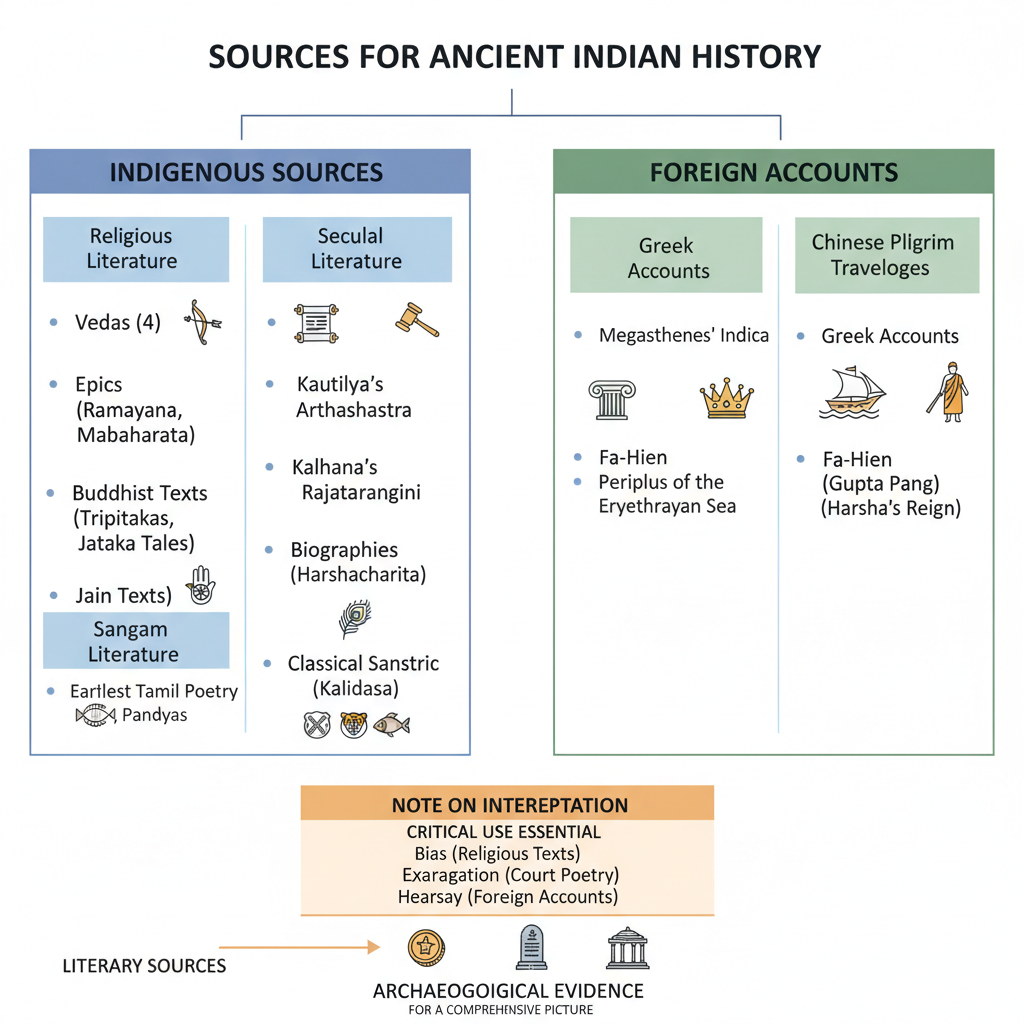

Literary sources for studying Ancient Indian History are broadly divided into Indigenous Sources and Foreign Accounts.

Indigenous Sources are the most extensive and can be classified into:

- Religious Literature: This includes Brahmanical texts like the four Vedas (providing insights into Vedic society), the Puranas (crucial for dynastic genealogies of the Mauryas, Guptas, etc.), the Epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata), and Dharmashastras (Manusmriti) which outline social laws. It also includes Buddhist texts like the Tripitakas (in Pali) and Jataka Tales (revealing contemporary social and economic life), and Jain texts like the Agamas (in Prakrit).

- Secular Literature: This category comprises non-religious works. Key examples are Kautilya’s Arthashastra, a detailed manual on Mauryan administration, and Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, a formal history of Kashmir. It also includes biographies like Banabhatta’s Harshacharita and classical Sanskrit works by authors like Kalidasa, which reflect Gupta-era culture.

- Sangam Literature: This earliest body of Tamil poetry is a primary source for the history of the South Indian kingdoms of the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas.

Foreign Accounts offer an invaluable outsider’s perspective. These include Greek accounts like Megasthenes’ Indica (describing the Mauryan court) and the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (detailing Indo-Roman trade), as well as Chinese pilgrim travelogues from Fa-Hien (Gupta period) and Hiuen Tsang (Harsha’s reign).

A Note on Interpretation

While these literary sources are essential, historians must use them critically. Many religious texts have a theological bias, court poetry (like charitas) contains exaggeration, and foreign accounts can be based on hearsay or cultural misunderstandings. Therefore, these sources are always studied in conjunction with archaeological evidence (like inscriptions, coins, and monuments) to build a more accurate and comprehensive picture of the past.